After building the SaguaroChem dataset by extracting chemical reaction data from the patent literature, we took a step back to evaluate how we could improve our extraction pipeline – specifically aiming to enhance the coverage, quality, and format of the data we extract from chemical synthesis documents. With a solid foundation in patents, we set our sights on a new and promising domain: chemical reaction data from the academic literature.

The academic literature is rich with novel chemistry – diverse substrates, unique transformations, and cutting-edge methodologies. But it also comes with its own set of challenges. Unlike patents, which tend to follow more standardized formats, academic articles vary widely in how reactions are described, making automated extraction significantly more difficult.

The Challenge: Variability in Reporting

One of the biggest hurdles we’ve encountered is the sheer variability in how reactions are reported in academic publications. Some authors provide detailed experimental procedures with IUPAC names for every reactant, reagent, and product. Others include only the product structure and characterization data, leaving the rest to be inferred. Most papers fall somewhere between these two extremes.

In our effort to extract as many reactions as possible from academic literature, we identified two of the most common reasons extraction fails:

- Structures without names: Compounds are often shown only in reaction schemes or molecular diagrams, with no accompanying name or textual reference.

- General procedures: Authors frequently describe a protocol once, then refer back to it throughout the paper (e.g., “Compound 3e was synthesized via General Procedure B”), requiring contextual linkage to reconstruct the full reaction.

Extracting Chemistry from Images

Chemists often rely on images to communicate chemical information – reaction schemes, molecular structures, and conditions – because they’re more concise and intuitive for human readers than long, complex IUPAC names. However, what’s easy for a human to interpret can be very challenging for a computer.

This makes image processing a critical component of our reaction extraction pipeline. Our system processes images in three main steps:

- Segmenting pages to identify and extract images on each page..

- Parsing where the important information such as molecular structures, reaction conditions, reaction schemes, etc., are in each image.

- Translating molecular images to SMILES and OCR’ing text.

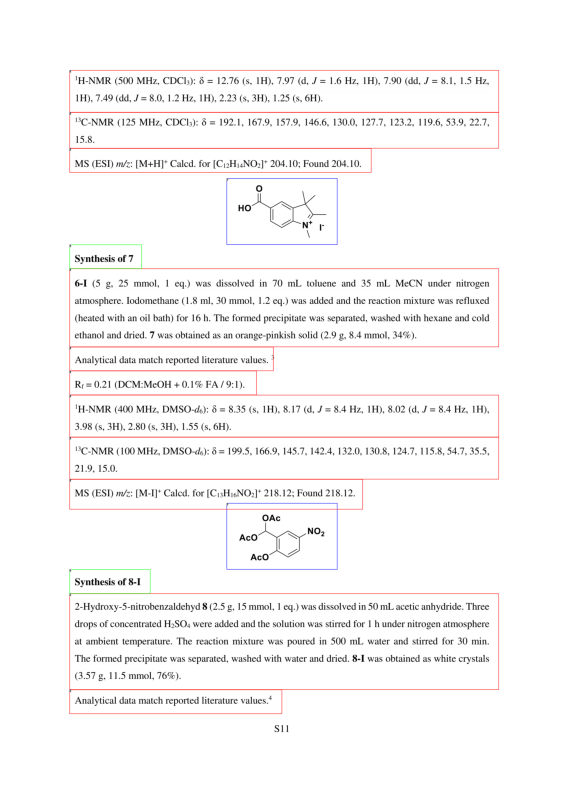

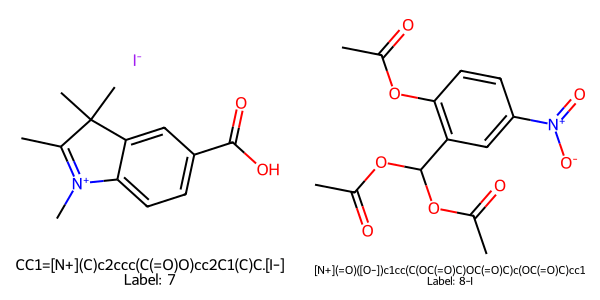

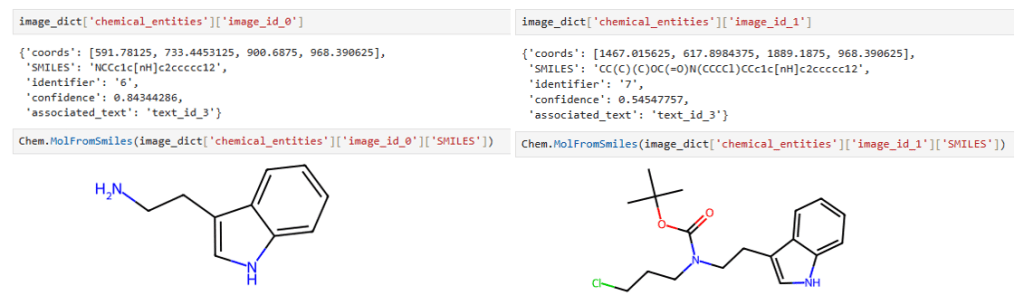

Figure 1 demonstrates the importance of image processing in chemical reaction data extraction. The two passages on this page would not be resolvable without the ability to extract information from images, but our infrastructure correctly segments the page to identify the molecular structures, translates the images to the correct SMILES, and correlates them with the correct products, 7 and 8-I respectively:

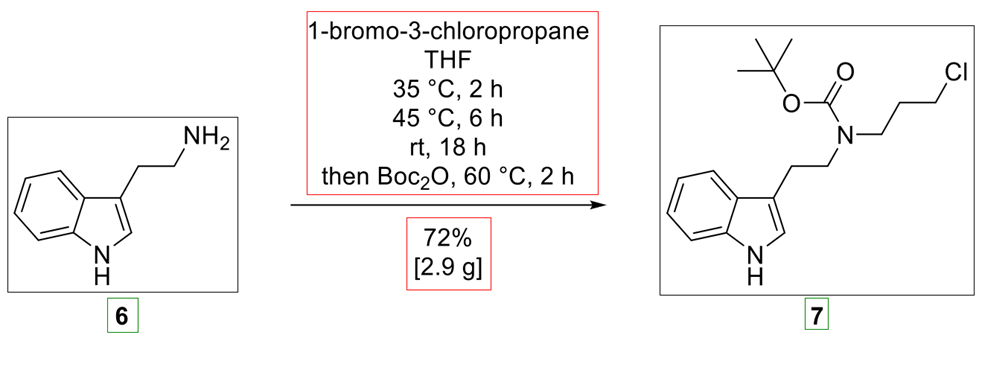

Our image extraction pipeline is also capable of handling chemical reaction diagrams, correctly identifying reactants, conditions, products, and molecule labels, such as in the example of Figure 3.

Making Sense of General Procedures

General procedures are another example of something that is trivial for a chemist reading a paper to understand, but that wreaks absolute havoc for automated extraction.

You’ll see something like:

“Compound 4h was synthesized from 4g using General Procedure B.”

Then you have to go back five pages to find:

“General Procedure B: A solution of the appropriate aryl bromide (1.0 mmol) and Pd(PPh₃)₄ (5 mol%) in toluene was stirred at 110°C for 16 h…”

If you don’t connect 4h to that procedure, you’re left with a compound and some characterization data and no reaction. But if you can make that link – say, by recognizing the phrase “General Procedure B,” finding its definition, and combining it with the specific reactants for 4h – you can reconstruct a complete reaction.

We’ve built infrastructure to do exactly that. Our system:

- Identifies general procedures and stores their definitions.

- Detects references to those procedures throughout the text.

- Infers connections when references aren’t explicit, using positional and contextual cues (e.g., proximity in the document).

In cases where general procedures are explicitly named, a name-based approach works well. But when references are implicit, we use document structure and layout to infer the correct association – e.g., assuming a compound description refers to the nearest preceding general procedure.

Why It’s Worth the Trouble

Just by implementing these two methodologies, we find that our extractions become much more complete and accurate. Instead of only capturing reactions that are neatly packaged and explicitly described, which represent just a small percentage of the all reactions in the academic literature, we can now recover the more implicit ones – those where the relevant information is distributed across figures, procedures, and scattered references.

This significantly increases both the quantity and quality of reactions we can extract, especially from papers that would otherwise yield very little structured data.

Final Thoughts

No one writes papers with the goal of making them hard for machines to read. Chemists write for other chemists, and the goal is clarity for human readers – not algorithms. But as the field moves deeper into data-driven chemistry – from reaction prediction to synthesis planning to automated retrosynthesis – the need for structured, machine-readable data is only going to grow.

Our infrastructure is built to bridge that gap. By combining image analysis, text parsing, and contextual reasoning, we’re making it possible to extract high-quality reaction data from even the most complex and inconsistently formatted documents.